Score

Ludwig Göransson

To create the score for Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan turned again to Oscar®-winning composer Ludwig Göransson. “Ludwig’s work on the film is both deeply personal and historically expansive,” Nolan says. “It achieves the effect of building out an emotional world to accompany the visual world that Ruth De Jong designed and Hoyte van Hoytema shot, and it draws the audience into the emotional dilemmas of the characters and their interactions with the vast geopolitical situations that they’re confronting.”

Nolan says he had no preconceptions about the music for the film, but he did offer Göransson an idea for a starting point. “I suggested he base the score on the violin,” Nolan says. “There’s something about the violin to me that seemed very apt to Oppenheimer. The tuning is precarious and totally at the mercy of the playing and emotion of the player. It can be very beautiful one moment and turn frightening or sour instantly. So, there’s a tension—a neuroses—to the sound that I think fits the highly strung intellect and emotion of Robert Oppenheimer.”

Göransson, inspired by Nolan’s suggestion and the vivid imagery he witnessed during the early stages of pre-production, embarked on a creative exploration, harnessing the expressive potential of the violin. Driven by an unwavering desire to capture the delicate intersection between beauty and dread, Göransson’s creative endeavors manifested in an array of captivating experiments. Techniques such as the incorporation of microtonal glissandos were deftly employed to expand the sonic palette, infusing the music with an ethereal quality. Collaborating with esteemed musicians from the Hollywood Studio Orchestra, Göransson began shaping Oppenheimer’s musical world with an intimate solo violin performance, capturing the essence of the character. As the story evolved, the ensemble gradually expanded to include a quartet, octet, and ultimately a large ensemble of strings and brass. This progressive orchestration reflected the deepening complexity of Oppenheimer’s journey, enriching the musical tapestry with each new addition.

Sound

Richard King

Four-time Oscar® winning Sound Designer and Supervising Sound Editor Richard King embraced the unprecedented creative demands of Oppenheimer, among them the ambition to create the sound of an atomic detonation, the sound of quantum particles and waves, and to create a sonic field for a film that reaches across time and location, communicating emotional elation and devastation. “Oppenheimer himself studied some of the largest phenomena in the universe down to the smallest, and Christopher Nolan wanted to exhibit that range of scale and give the audience a visceral sense of the enormous power that’s latent in quantum particles, which is ultimately revealed in the Trinity test,” King says.

“For the Trinity test explosion, my inspiration was a sound that has occurred on rare occasions in nature,” King says. “I found a recording of one of these events to use as reference. There are a number of elements, all chosen to help achieve this sound, which almost sounds like an enormous cosmic door slamming. The Trinity test explosion needed to be a sound unlike any other explosion. That sound of the detonation is further heightened by both the silence that precedes it, and the analog sounds of the equipment being used in the bunker prior to the detonation.

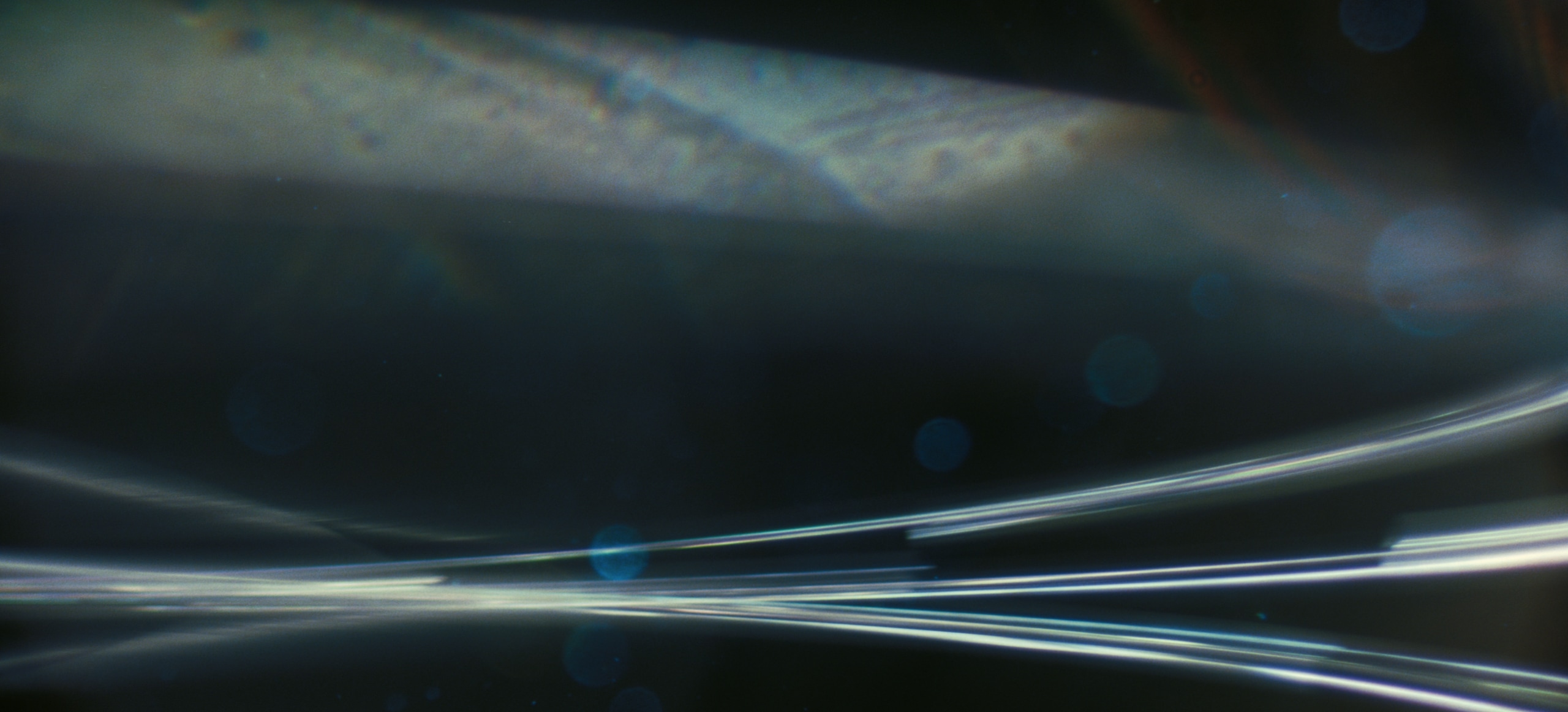

At the other end of the sonic spectrum, the sounds that only J. Robert Oppenheimer himself can hear also relied on an organic design approach. “Quantum particles and quantum waves haunt Oppenheimer’s imagination when he visualizes their immense latent power,” King says. “There was nothing exotic in this sound. We just kept fiddling around until something stuck. Christopher Nolan created all those visuals practically; they’re not CGI. We worked with the same philosophy and created the sounds by manipulating natural sound elements.”

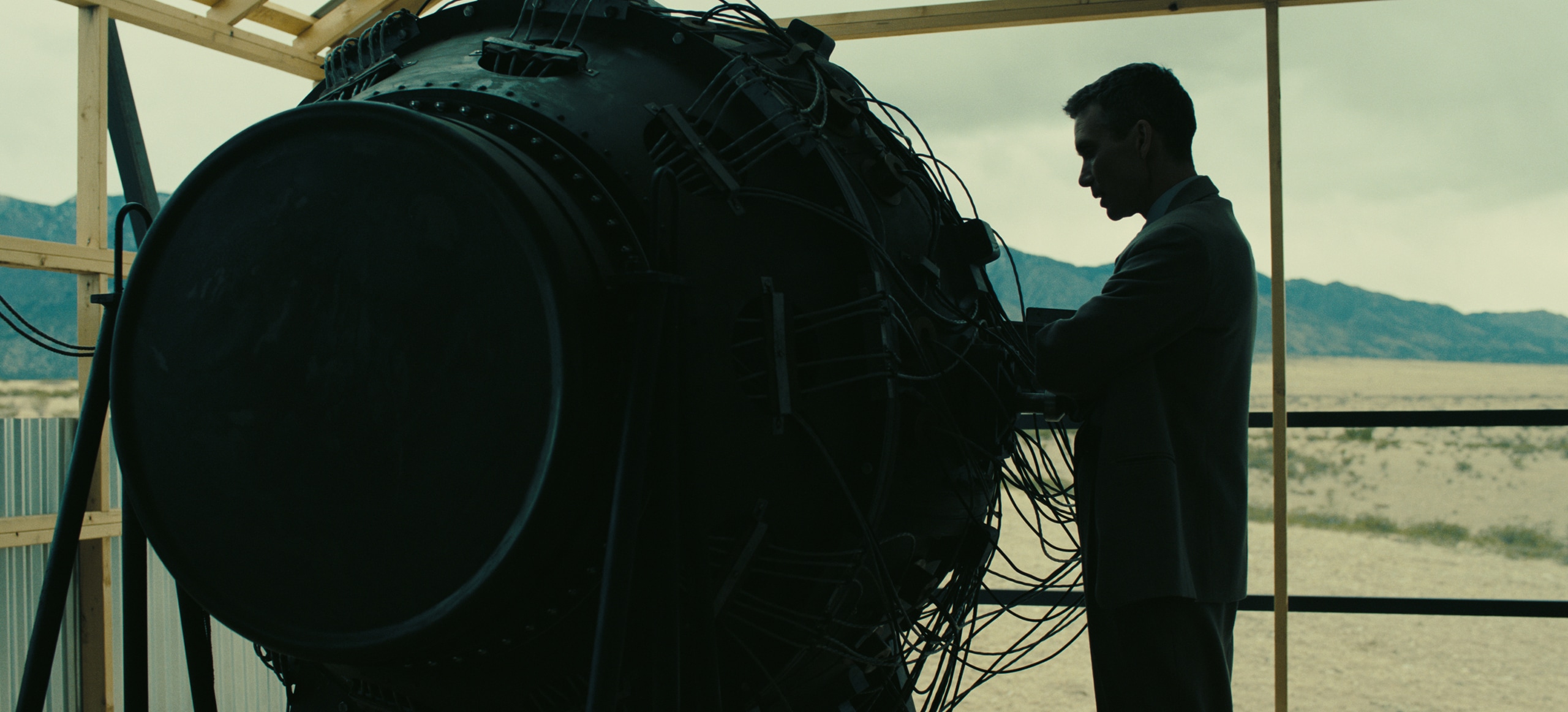

Production Design

Ruth De Jong

Los Alamos

The Trinity Test Site