Cinematography

hoyte van hoytema

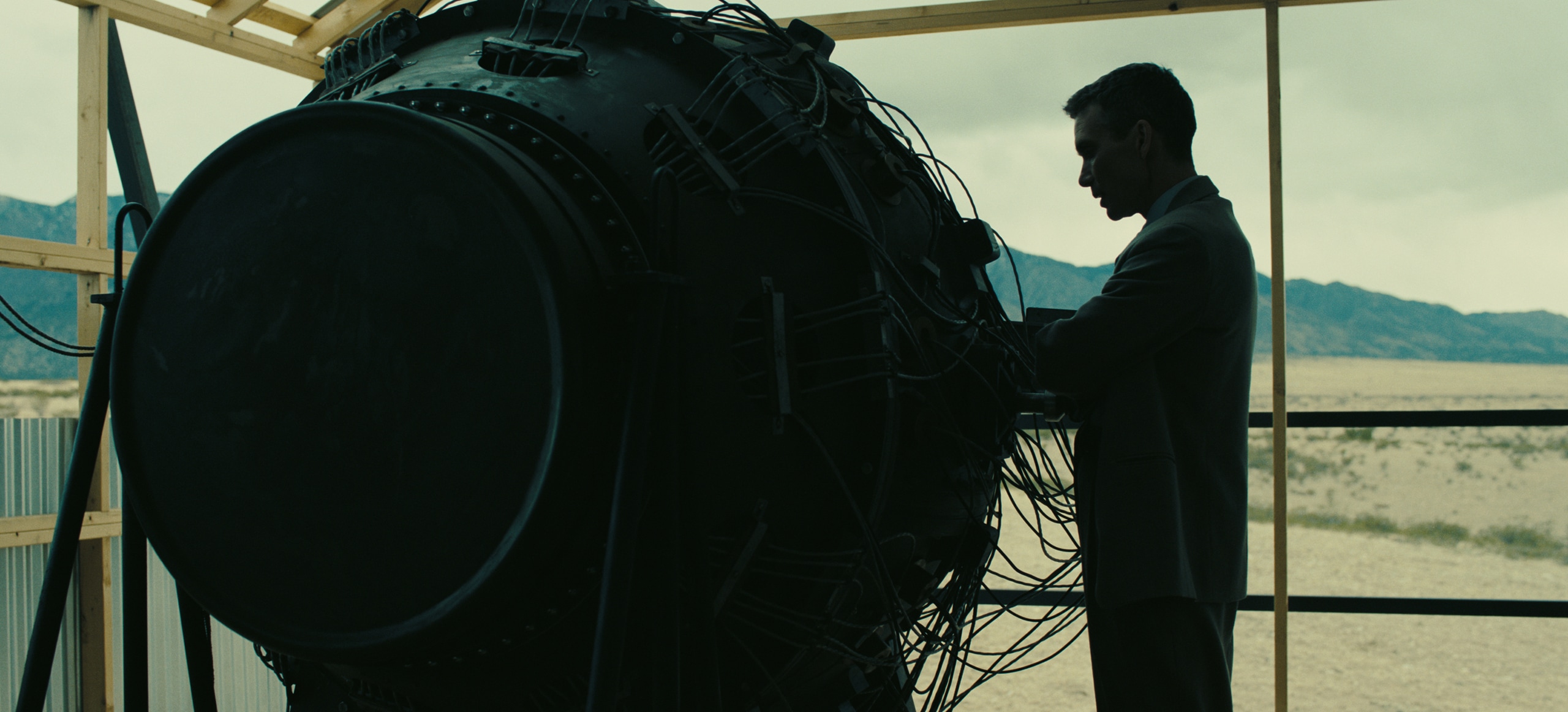

Oppenheimer marks the fourth collaboration for Christopher Nolan and cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema. “The style of photography that Hoyte and I adopted for this movie was to be very simple yet very powerful,” Nolan says. “No barrier between the world of the film and the audience, no obvious stylization other than the black-and-white sequences. But particularly with the color sequences, we wanted very unadorned, simple photography, as natural as possible, revealing lots of textures in the world. Whether it’s the costumes or the sets or locations, you’re looking for real world complexity and detail.”

Oppenheimer was shot exclusively with large format cameras—Panavision® 65mm and IMAX® 65mm. “What large-format photography gives you is clarity, first and foremost,” says Nolan. “It’s a format that allows the audience to become fully immersed in the story and in the reality that you’re taking them to. In the case of Oppenheimer, it’s a story of great scope and great scale and great span. But I also wanted the audience to be in the rooms where everything happened, as if you are there, having conversations with these scientists in these important moments.”

The black-and-white scenes required the invention of a new kind of film stock. “One of our first phone calls was to Kodak,” says van Hoytema. “We asked: ‘Do you have 65-millimeter black-and-white film?’ And of course, they didn’t, because they never made it before. So, we asked: ‘Can you make it?’” And they were like, ‘Maybe?’ And then we were always nagging them like little kids to do it. Fortunately for us, they really stepped up to the challenge. They supplied us with prototypal film stock—freshly manufactured, with hand-written labels on it—and when we tested it, the first time we saw it, it just blew us away. It was so special and so beautiful.”

Editing

Jennifer Lame

For Oppenheimer editor Jennifer Lame, A.C.E., the film was a dream assignment in a way: an entire film of people in rooms talking.

The mastery of Lame’s work on the film can be seen in the thrust and propulsion of a film that contains relatively little action. The film moves, thrums, even when the characters are physically static. The key, Lame says, was not staying too long in one place, cutting to different characters, perspectives and angles in a room, rather than “lingering on a shot because of its quality or composition.” Without that movement, the film can begin to feel weighted down. “When you’re dealing with a three-hour biopic based on a ginormous topic, and a ginormous book, pacing is a problem,” Lame says.

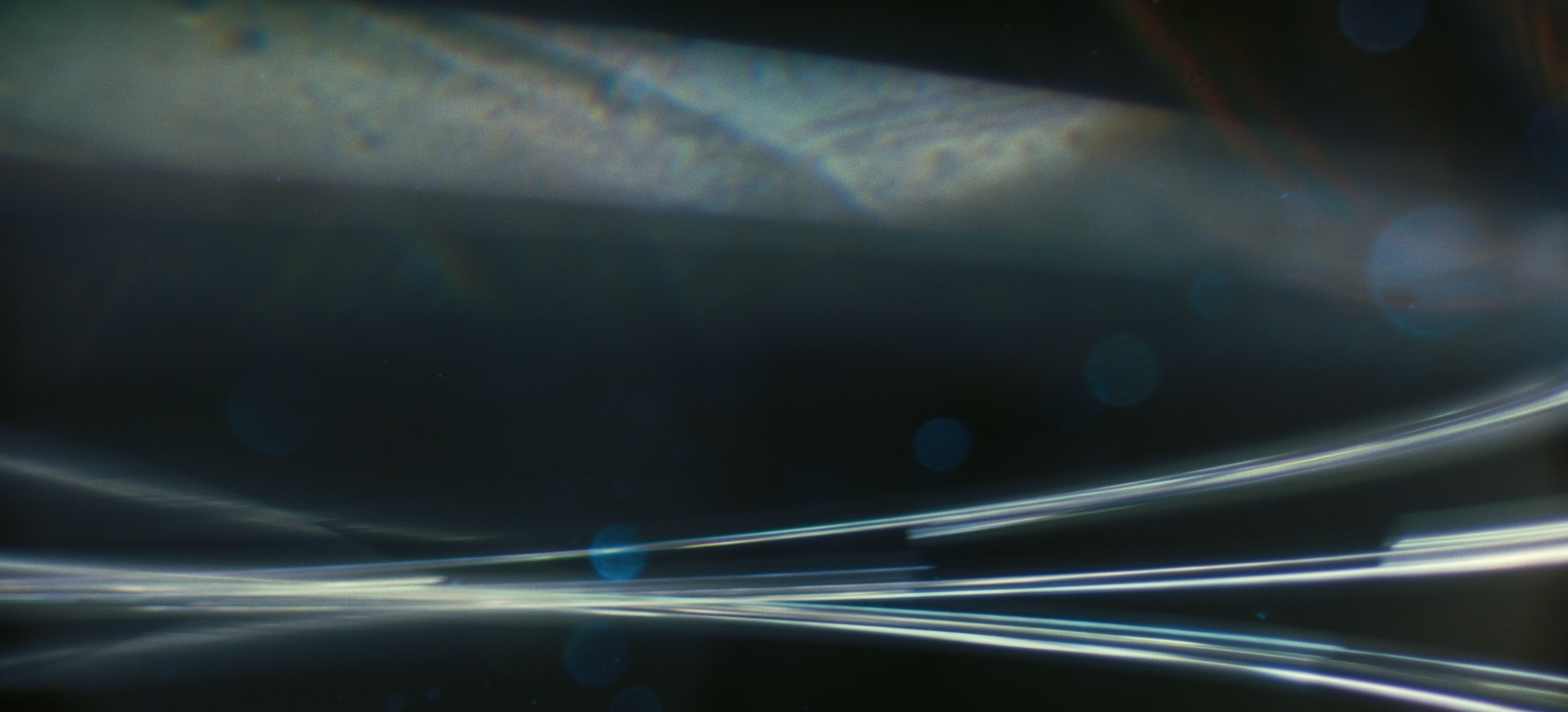

Throughout the film, the scenes of people talking are lined with sound and imagery from inside Oppenheimer’s mind, particles and waves that only he can hear and see. Lame says that the process of editing those elements relied on intuition and an internal cadence. “Those [elements] were written into scenes, but there was a creative process of figuring out when and how to cut those in,” Lame says. Much of it was fluid and difficult to explain. “It’s very hard to talk about editing on some level, because you try things in terms of rhythm, and it’s like trial and error.”

Visual Effects

Scott Fisher & Andrew Jackson

Contrary to Internet rumor, Christopher Nolan did not detonate an actual atomic bomb in New Mexico for Oppenheimer, just so he could film the nuclear fire and mushroom cloud of the iconic Trinity test. Instead, Nolan and cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema worked with special effects supervisors Scott Fisher and Andrew Jackson to produce the film’s version of atomic explosion. Nolan gave them a limitation: Consistent with his aesthetic preference for practical effects, Nolan told them there could be no computer-generated imagery.

Jackson and Fisher began conducting experiments—smashing ping pong balls together, throwing paint at a wall, concocting luminous magnesium solutions, and more—and filming them on small digital cameras super close-up at various frame rates. “Then we’d show it to Chris,” says Fisher, “and he’d say, ‘Yeah, that’s the right idea. Now figure out how to shoot it massive with IMAX® cameras.’” How the actual atomic explosion images were created for the film remains top-secret, but it’s clear the work of making them was a Manhattan Project unto itself, and a rather fun one, too.

Some of the techniques that Nolan’s f/x team used to produce the spectacle of nuclear fission were also used to help create the scenes that portray Oppenheimer’s inner world. Again, Nolan placed a premium on practical effects and eschewed CGI. “There’s one sense in which computer graphics is the obvious way to do it, but I didn’t feel we were going to get anything that would feel personal and unique to Oppenheimer’s character,” says Nolan.

Costume Design

Ellen Mirojnick

Working with Christopher Nolan for the first time is legendary costume designer Ellen Mirojnick. “What I found really interesting about Oppenheimer’s story was learning how in-sync the geniuses of both Oppenheimer and Christopher Nolan were in exploring an unknown landscape through the experimentation of fission and fusion, literally and figuratively,” says Mirojnick.

Mirojnick designed Cillian Murphy’s Robert Oppenheimer costumes to reflect a man whose fine tastes were clearly defined through his haberdashery. His appeal was accented by the choice of blue hues used for his shirting, illuminating his piercing blue eyes. Oppenheimer curated the same silhouette throughout his life. Mirojnick, through her research, found that his weight was the only thing that affected the silhouette, which appeared “more voluminous during the period which saw the detonation and effects of the bomb,” says Mirojnick. “His style, however, remained constant throughout.”

Key to the Oppenheimer silhouette was his hat. It took Mirojnick and her team some time to source its origin. Mirojnick reached out to hatmakers in New York and Italy to recreate the infamous shape, but it was Baron Hats, the legendary Hollywood hat maker, that recreated the hat to perfection.

Hair & Makeup

Jamie Leigh McIntosh & Luisa Abel

For Oppenheimer, head of hair design Jamie Leigh McIntosh and Head of Make-Up design Luisa Abel collaborated closely with Director of Photography Hoyte van Hoytema and costume designer Ellen Mirojnick to create the look of each actor.

Luisa Abel says that with a story that spanned four decades, featuring historic and iconic figures, filmed on 70mm IMAX, the make-up design and execution had to be seamless to allow the audience to journey into this world.

For Jaime Leigh McIntosh, her first hair design discussions with Nolan were on how best to hit the hairstyle/length marks with Oppenheimer himself, showing the passage of time without the use of multiple wigs. Once they had a plan for J. Robert Oppenheimer, they would then extend that same strategy to the other characters.